Capitol Reef: See Rock Formations and Highlights In A Day

The vast geological features of Capitol Reef National Park make it impossible to see everything in a day. But one day will allow you to see the highlights.

In addition to the formidable rock formations, the southern Utah park has several Mormon pioneer and Native American historical sites.

The long, slender park stretches about 65 miles from the north to the south and is only a few miles wide throughout most of the park. The main road, state Route 24, runs east and west through the most visited area of the park, the Fruita District.

If you have a couple extra days, explore the less visited Cathedral Valley and Waterpocket districts. You’ll need a high-clearance vehicle for Cathedral Valley.

Sticking to the Fruita District, there is much opportunity to learn about Native American and Mormon history and culture here. And the geological features are beyond impressive.

How Capitol Reef Got Its Name

Capitol Reef got the first part of its name from the white domes of Navajo Sandstone resembling the domes of capitol buildings. The second part of the name, “Reef,” came from the rocky cliffs that form a barrier like ocean reefs. Geology – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

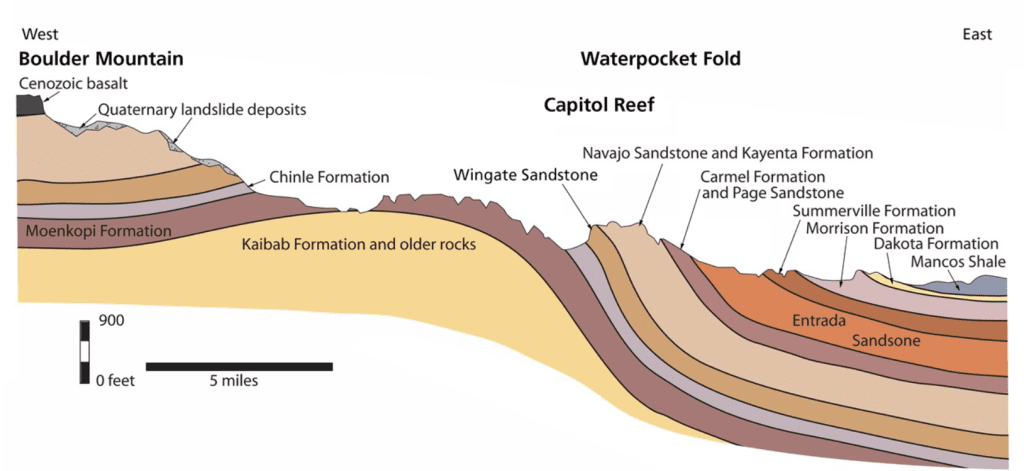

Between 270 and 80 million years ago, about 10,000 feet of sedimentary rock layers deposited on the region, then lifted thousands of feet due to plate tectonic forces, according to the park website. The Waterpocket Fold, as it’s known, is a 100-mile warp in the earth’s crust that goes through the park from the north to the south. Geology – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Waterpocket Fold Defines the Park

Capitol Reef is unique in its formation due to the Waterpocket Fold. Unlike much of the Colorado Plateau which lifted evenly (like the Grand Canyon), the Waterpocket Fold shifted the western side of the park upwards along the fault. The western side is 7,000 feet higher than the east side forming a monocline or step-up formation in the rock layers. Geology – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

The diagram below shows the uplift of sedimentary rock, followed by years of erosion, creating the cross-section of rock formations seen today.

To visit the Waterpocket District, pick up the “Loop the Fold Road Guide” at the visitor center. A good portion of the loop is outside the park boundaries. According to the guide, the 125-mile driving tour takes about four hours, more with stops and hikes.

First time visitors who only have a day usually explore the Fruita District. First, stop to get a brochure and ask questions at the visitor center located near the west side park entrance.

Hike to Hickman Bridge

If you enjoy hiking, drive a few miles east to do the popular Hickman Bridge Trail. This moderately difficult hike, with about 400 feet of elevation change, is just shy of a mile each way. Trail Guide – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

You can walk underneath the 133-foot-wide bridge which has beautiful views from both sides. The hike also has gorgeous views of the canyon, Navajo Dome, and non-native igneous rock.

Navajo Dome and Black Boulders

Black boulders are scattered through the hillside, like seen in the picture below. Originally from basalt and andesite cliffs of the Boulder and Thousand Lakes mountains west of the park, it is believed these boulders moved to this area in large landslides and flash floods. Black Boulders – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Along Hickman Bridge Trail you’ll see Navajo Dome. The dome looks more like a pyramid than a dome with its pointy top. Consisting of Navajo Sandstone, the dome formed from a windblown dune field thought to be the largest erg (sand sea) in history, according to the “Loop the Fold Road Guide.”

The guide, by the Capitol Reef Natural History Association, explains the vertical lines seen are cracks created during rock bending from the uplift of the Waterpocket Fold. In addition to wind erosion, a sign along the Hickman Bridge Trail notes that the monsoon rains caused sediments to scour the sides of Navajo Dome, creating its features.

The Fremont River, seen at the beginning of this hike, runs through the park, parallel to Route 24.

Fremont Culture Petroglyphs

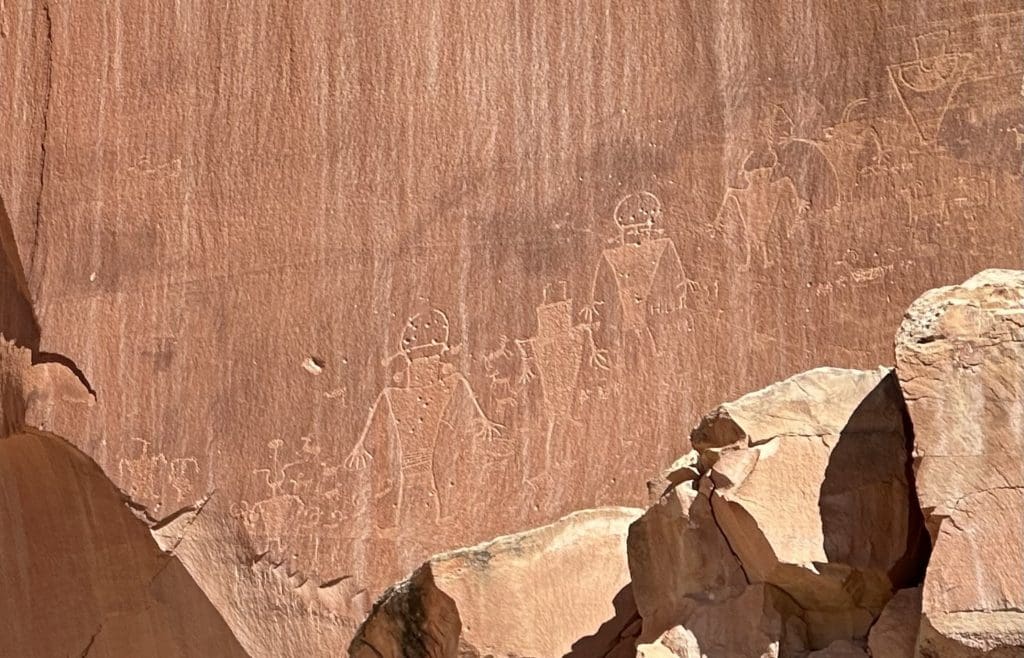

Next stop is the Fremont Culture Petroglyph Panel visible from two easy-to-walk boardwalks. Archeologists named the prehistoric people, who lived in the area from 300-1000 AD, the Fremont Culture due to the proximity of the Fremont River Canyon. fremont culture petroglyphs – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

You’ll get a better view with binoculars but can see the sketches with the naked eye. Look for carvings of human-like figures, bighorn sheep, other animals, and geometric shapes on the side of the cliff. A sign posted on the boardwalk will point where to look.

Look Inside Fruita Schoolhouse

Also, off Route 24, stands a restored one-room schoolhouse below the Wingate Sandstone cliffs in its original site. Fruita Schoolhouse – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Mormon settlers built the one-room schoolhouse in 1896, two years after the schooling began in Junction (now called Fruita). Classes continued until 1941. Fruita Schoolhouse – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Eight grades were taught once farming needs were met, according to a sign at the site. In addition, the log structure was used for community gatherings, church services, meetings, dances, and elections. Fruita Schoolhouse – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Mormon pilgrims planted apple, apricot, cherry, peach, pear, and plum trees in the river valley between the 1880s and 1960s, according to a park sign, which providing food and income for the residents.

Thousands of fruit trees were planted throughout the park, the sign notes, which are now maintained by park staff using the same flood irrigation ditches dug in the 1880s. Wherever there is a sign posted, “U-Pick Fruit,” visitors can pick the ripe fruit.

Stop by Gifford Homestead

After the visitor center, stop at the Gifford House, famous for its pie, and open from Pi Day, March 14, to late November. (We just missed the season opener.)

The Gifford Homestead is an early Mormon settlement, which includes a barn, smokehouse, garden, and pasture. The original home was built in 1908, with the last Fruita residents, the Gifford family, living there until the National Park Service purchased the property in 1969. Gifford Homestead – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Explore Scenic Drive

If you only have one day at Capitol Reef, make it a priority to drive on the 7.8-mile Scenic Drive. The colors and formations of sedimentary rock on the western side of the Waterpocket Fold are unique and different depending on where you are on Scenic Drive.

You might notice tall reddish-brown towers of shale. Formed from silt and clay, laid in moist climate over 225 million years ago, these Moenkopi Formation are more than 950 feet thick in spots. Guide to the Scenic Drive – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Above the Moenkopi Formations are bands of gray and burgundy layers that contain volcanic ash, according to the website, and are stunning around the entrance to the Grand Wash.

Above the colorful volcanic ash is the Chinle Formation, a rock rich in petrified wood, and at Grand Wash ascends a sheer cliff wall. Guide to the Scenic Drive – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Turn Down Grand Wash Road

Drive down the dirt road of the Grand Wash. The road winds through the narrowest part of the canyon and leads to hikes to Cassidy Arch and the Grand Wash Narrows.

Walk on the Grand Wash Trail to access the Cassidy Arch Trailhead and the Grand Wash Narrows.

Cassidy Arch Best Trail in Capitol Reef

Past the parking lot, it’s about a quarter mile to the Cassidy Arch Trail. Once you reach the trailhead, it’s another 1.5 miles, one way, with a strenuous 950-foot elevation gain.

The hike is worth the view when you get to the top of Cassidy Arch. You can walk on top of the arch if you aren’t afraid of heights.

Cassidy Arch was named after the outlaw Butch Cassidy thought to have spent time here hiding from the law. Guide to the Scenic Drive – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Drive Back In Capitol Gorge

At the end of Scenic Drive, you’ll come to another dirt road leading into Capitol Gorge. Before getting to the narrowest section, you’ll see Golden Throne, another dome-like rock formation.

The 2.4-mile Capitol Gorge Road has unbelievably beautiful views of the canyon walls as you drive through the gorge.

Driving back through Scenic Drive you might notice formations you missed coming through the first time, like the Egyptian Temple.

Once off Scenic Drive and back onto Route 24, head west to see the rest of the park.

Goosenecks Overlook in Capitol Reef

The view of Goosenecks Overlook is a short walk from the parking lot.

Not to be confused with Goosenecks State Park near Mexican Hat, here you can view Sulphur Creek bending through the canyon like a snake.

Panorama Point

One of the most beautiful panoramas in the park is at Panorama Point.

If you have an extra day, visit Cathedral Valley.

Cathedral Valley District

The Cathedral Valley Driving Loop, on the northeast side of the park, is just over 57 miles long but takes six to eight hours in a high-clearance vehicle. Most people, according to the park website, drive clockwise starting at Hartnet Road about 12 miles east of the visitor center, then circle back on Cathedral Road. Cathedral Valley – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Vehicles must ford the Fremont River near the south end of Hartnet Road—there is no bridge across the water. Normally the river is a foot or less at this point, but if in doubt of the road conditions call 435-425-3791 or stop by the visitor center. Do not cross when the water is high. Cathedral Valley – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

The colorful Bentonite Hills are part of Cathedral Valley. Highlights on the drive include the lower South Desert Overlook, Upper Cathedral Valley Overlook, Morrell Cabin, Gypsum Sinkhole, Temples of the Sun and Moon, and Glass Mountain.

Bentonite Hills

If you can’t do the Cathedral Valley Loop, you can still see a portion of the Bentonite Hill east of the park about two minutes from the Capitol Reef National Park sign on Route 24. The Bentonite Hills, made up of Brushy Basin shale, are a member of the Morrison Formation. Bentonite Hills (U.S. National Park Service)

The colorful banded hills formed during the Jurassic Period when mud, silt, fine sand, and volcanic ash deposited in swamps and lakes, according to the National Park Service site. Since Bentonite clay (altered volcanic ash) becomes slick and gummy when wet, drive only on the road and hike only on previously disturbed areas and wash bottoms. Bentonite Hills (U.S. National Park Service)

Mammals in Capitol Reef

Capitol Reef is home to 58 mammal species, including desert bighorn sheep, mule deer, mountain lions, gray fox, American beavers, ringtails, yellow-bellied marmots, and 19 species of bats. Mammals – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

The park has over 250 species of birds, with popular sites including the Fremont River Trail near the orchards and campground, Ripple Rock Nature Center, and along Sulphur Creek. Birds – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

There are 10 species of lizards and six species of snakes in Capitol Reef, including one venomous, the midget-faded rattlesnake. The common kingsnake, also in the park, prey on rattlesnakes. Snakes tend to bask in the sun or hide in rock crevices, so watch where you put your feet and hands. Reptiles – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

Know Before You Go:

- To enter the park, you need a pass or pay admission. Timed tickets are not required. Certain activities need permits.

- There are no lodges in the park, yet hotels and other accommodations are located nearby in Torrey.

- There is a high demand at the Fruita Campground, which has 71 developed sites, each with a picnic table and fire pit with grill. The sites have no individual water, sewage, or electric hookup. There is a dump station and potable water fill station. Restrooms have flush toilets, running water, but no showers. Fruita Campground, Capitol Reef National Park – Recreation.gov. Site must be reserved on https://www.recreation.gov.

- Two primitive campgrounds, at Cathedral Valley and Cedar Mesa, offer a picnic table, fire grate, pit toilet, but no water. Check road conditions first by calling 435-425-3791. Primitive Campgrounds – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

- Horses and other pack animals, like burros and mules, are allowed in certain areas of the park. Recommended rides for pack animals include Halls Creek in the Waterpocket District, South Desert in the Cathedral Valley, and South Draw Road. For more information on pack animals, check out the following website. Horse & Pack Animal Use – Capitol Reef National Park (U.S. National Park Service).

For more information about Utah parks, check out stories on Arches Arches National Park Has Largest Concentration of Arches – Travel Like A Tourist, Bryce Canyon Bryce Canyon Has Largest Collection of Hoodoos – Travel Like A Tourist and Canyonlands. Canyonlands’ Rugged Terrain Is Best Explored By 4WD Vehicle – Travel Like A Tourist